Gender politics (‘dʒɛndə ˈpɒlɪtɪks)

noun.

The assumptions underlying expectations regarding gender difference in a society; (also with singular agreement) an ideology based on such assumptions.

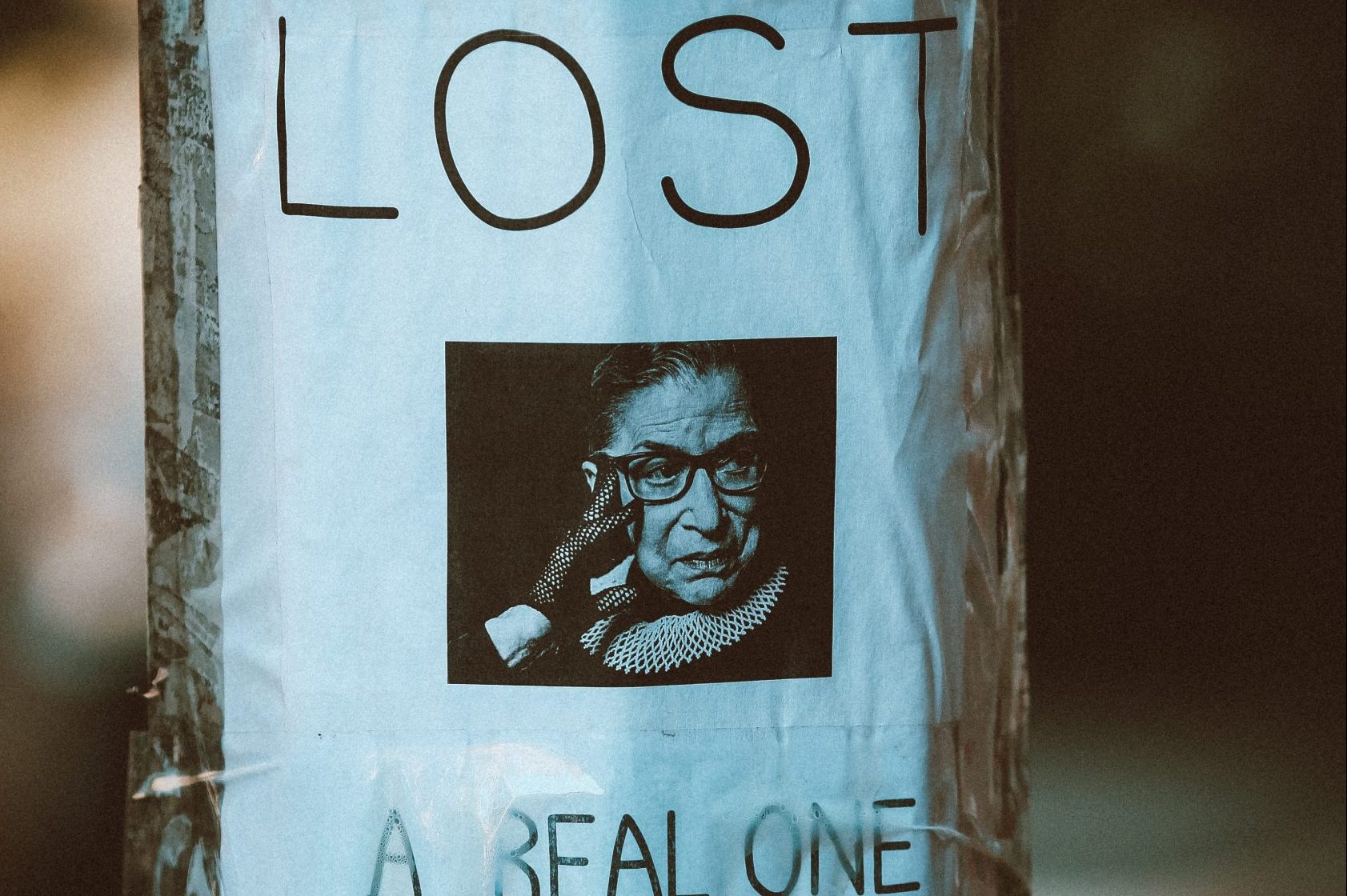

On the 18th of September 2020, the world saw the loss of a prominent Supreme Court Justice, who dedicated her life advocating for women’s rights in America. As a litigator and the second woman to sit on the high court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg restructured the traditionally male-centric views of the American law.

Even before being appointed as the Justice, Ginsburg continuously challenged the societal views of women. Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1956, where she was one of the nine women among a class of five hundred students. Nonetheless, this apparent gender imbalance didn’t stop her from becoming the first female member of the Law Review. When she later transferred to Columbia University Law School due to her husband’s job in New York City, she graduated as the joint top student of her class and accepted a clerkship with a Manhattan federal judge. In 1963, Ginsburg entered the faculty of Rutgers Law School in Newark, New Jersey, where she became one of the few women to teach at any American law school. Afterwards, she joined the Columbia Law School faculty in 1972, where she co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) Women’s Rights Project, which participated in nearly 300 gender discrimination case by 1974. While teaching as a tenured professor, she argued six cases before the Supreme Court – among which she won five.

When Ginsburg started working in the 1960s, the Supreme Court never invalidated any laws that were discriminatory by sex, and rejected any proposals which sought for equal treatment of all genders. For instance, in Bradwell v. Illinois (1873), the Supreme Court determined that the right to practice a profession was not among the privileges of the Fourteenth Amendment, and refused to provide Myra Bradwell with a licence to practice law in that state, due to her gender. In the 1908 case Muller v. Oregon, the Supreme Court upheld the law in Oregon, which limited the number of hours women could work, unlike men. During this case, the attorney for the state, Louis D. Brandeis argued that women needed “special protection”. He also issued a 113-page document on the negative effects of long working hours, with a particular emphasis on the reliant and biologically reproductive roles of women. Hence, the mid-twentieth century was a time when the legal system categorised and perceived women by their gender stereotypes.

One of the most significant cases that Ginsburg was involved in during the 1970s with the ACLU was Reed v. Reed (1971). This case concerned two divorced parents, Sally and Cecil Reed, who both applied to administer their deceased son’s estate. When the judge appointed the father (since Idaho law overtly favoured men over women in administering the estates of people who die without a will), Sally Reed appealed to the Supreme Court. Although she didn’t argue in the case, Ginsburg successfully wrote a brief which convinced the court to invalidate the state’s preference for males. This case eventually extended the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to women. From her early career, Ginsburg thus sought to destabilise the legal system’s discriminatory treatment of women.

Ginsburg was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in June 1980, where she worked as an appellate judge for 13 years. She was then nominated by President Bill Clinton to serve in the U.S. Supreme Court in June 1993. On the court, the meticulous nature of her majority opinions and dissents became very well-known. For instance, Ginsburg wrote the majority’s opinion in United States v. Virginia (1996), highlighting the fact that the all-male Virginia Military Institute (VMI) violated the equal protection clause, by refusing to admit women. She rejected the VMI’s assertion that the military-focused programme is unsuitable to women and critiqued the institute’s overgeneralisation of all women as unfit for certain roles and courses. Throughout her judicial career, Ginsburg has undoubtedly been a leading figure in altering the American court’s perception of women, and encouraging a more impartial legal system for all, regardless of their gender.

Although we will no longer be able to see Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the Supreme Court of the United States, she will live on as an endless source of inspiration, courage, and hope to many. The remarkable path that she took to tackle gender inequality in the American legal system will be cherished forever.

This article was written by Olivia Kim, Publications Officer at King’s Women in Law (KWIL). KWIL is an inclusive society which celebrates women and diversity in all areas of law. If you would like to know more about their society, please feel free to visit their website and Instagram.

Publications Officer, King's Women in Law

0 Comments