Over decades it has become the norm in Hungary that doctors take multiple jobs – sharing their time between the public and private sectors. However, the latest healthcare reform’s goal is to make the passage between the two strongly intertwined sectors impossible, essentially causing discontent.

The recent healthcare legislation’s basis is a salary increase for doctors provided that they sign a contract.

The potential raise might be appealing – although doctors are unaware of how this contribution-based raise is calculated. However, even with a guaranteed raise, the contract’s collateral terms and conditions are worrisome. What the government expects in return places constraints on doctors as 22% of the capital city’s doctors have expressed that they would reject the contract.

The most controversial section of the legislation is the prohibition of relying on other income sources (even on not healthcare-related ones) without official permission if the doctors are under contract. To illustrate how this law restricts doctors’ opportunities, it implies that doctors – as government employees – cannot simply rent out a flat or become part-time vegetable-producers selling for the local market.

More than 50% of doctors have not one but at least two jobs with 43% working exclusively as public servants, leaving the remaining 57% as part-time private practitioners and/or employees of private hospitals. The legislation targets specifically those “commuting” between public and private sector jobs. 37% of doctors have a private clinic, which takes up significant time and is an equally significant income source of doctors. It is unlikely that they leave this practice behind, thereby resisting the restrictions imposed on part-time jobs.

Increasing the scope of the private sector is a likely reaction of doctors based on the Hungarian Chamber of Doctors’ survey. An overwhelming 77% of 7700 doctors’ responses indicated that they would not sign the current version of the contract to work in the public sector. 37.4% of those not signing the contract plan on working in the private sector while 35.3% consider leaving either the country or the profession. This would lead to shortages of doctors in public hospitals.

Restricting doctors’ opportunity to have side-jobs is unacceptable.

The Hungarian Chamber of Doctors found that 98.9% of the respondents believe that the law has to give people the freedom to decide on their employment. If they want to take on second jobs, they should be allowed to do so.

Patients in the public sector will incur the cost of the healthcare reform.

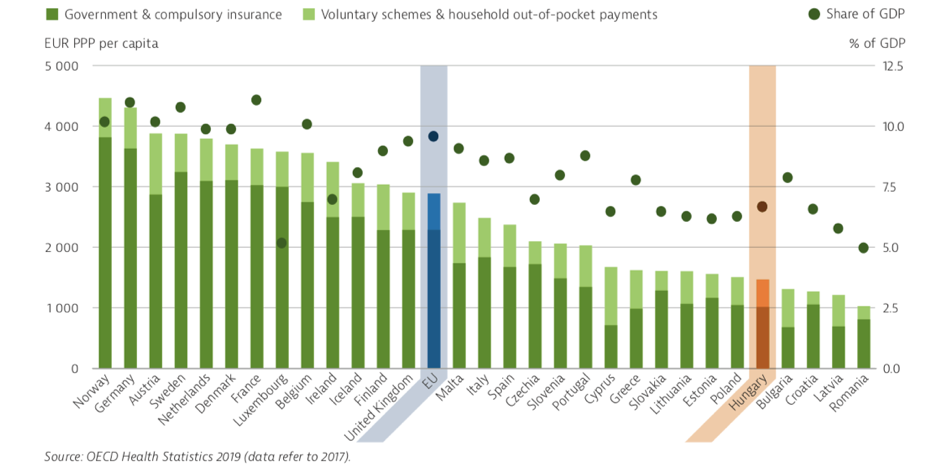

As the healthcare system already receives fewer funds than what the EU countries spend on healthcare on average, the waiting lists are long, and it is common that patients have to wait for months to get treatment in public hospitals. Doctors leaving the public sector would only aggravate the problem of long waiting lists.

This article focuses not on the details of the reform, but it reflects on doctors’ responses to the new legislation and how the welfare state might be affected. For decades, doctors have built up an intricate system in which they work at hospitals, private clinics, and do studies for pharmaceutical companies simultaneously to ensure a better living. They could go from the private to the public sector and vice versa with relative ease. This might sound greedy, but the assumption that doctors are rich is not true. One would not go from the hospital to a private clinic only to come home at 8pm if it was not deemed necessary.

Talking about welfare states

Welfare states exist to protect people against life uncertainties such as sickness, unemployment, and old age. However, the welfare states of the world could not be more diverse in every aspect, from financing to coverage and benefits, except for the unifying goal of insuring against risk. Ultimately, the quality by which the welfare state ought to be assessed is generosity. What benefits and services social policies include, whether they are accessible – all these add up to how much security they provide to counteract risks. Luckily, these aspects are considered as one analyses welfare state measures from the perspective of decommodification.

Decommodification

Esping-Andersen defines decommodification as ‘the extent to which individuals and families can maintain a normal and socially acceptable standard of living regardless of their market performance’. The idea is that survival should not depend on one’s participation and performance in the labour market, or to put it simply, on money.

The more decommodifying a welfare state is, the better it ensures that people are protected against risks even if their income is not substantial. If those who have worked for several years are the only people able to collect benefits to secure their livelihood during uncertain times, then market forces determine one’s fate. It follows that welfare states that provide help for all residents regardless of previous individual contribution are in stark contrast to the contribution-based systems. Furthermore, if only 50% of one’s salary is covered by the government then the worker will return to the market sooner because he/she does not have the luxury to secure his/her living without working.

Finally, when evaluating the welfare states’ capacity to allow people to opt out of the market, in-built disincentives have to be considered. An example would be the number of waiting days. In case the waiting period is long, access to support is hindered.

The main question is whether one can maintain a livelihood without the market.

Attacking generosity

Welfare state entails the delivery of services, such as healthcare, and not just cash benefits. While Esping-Andersen focuses on the latter, namely pensions and benefits, Bambra extends decommodification to healthcare. The decommodifying potential of the welfare state also depends on the extent to which medical treatment is secured independently from the market. If one is unable to cover medical bills, his life is at stake simply because he has not sold his labour enough. Whereas, the goal of public healthcare – the welfare state – is to provide medical procedures without the high costs associated with private provision of health services.

However, because doctors might leave hospitals and whole clinics might shut down due to a large proportion of doctors refusing to sign the contract, the waiting list would get even longer with cases piling up. Patients are already expected to wait for treatments longer than they should. Now it might become impossible to get adequate treatment in time. This delay is a first attack on the welfare state as it hinders access to proper healthcare.

The second attack stems from the longer waiting lists in public hospitals. If patients want to ensure their treatment, they have to pay substantial amounts and rely on the private sector. Private clinics will become more popular due to the improper condition provided by the government-financed public sector. If people pay out-of-pocket, the decommodifying potential of the welfare state suffers as people have to rely on labour market participation. As Bambra says, the degree of healthcare-decommodification shrinks with the size of the private sector.

Thanks to the government’s legislation that effectively constrains doctors’ freedom, how quickly patients get treatment now depends on whether they can afford private doctors.

2nd year Political Economy student at KCL

0 Comments