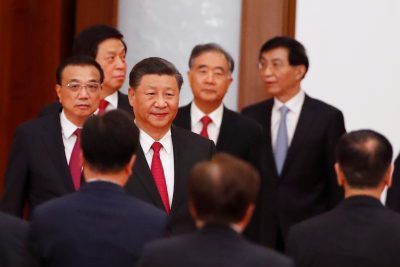

On the 23rd of October the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party came to a close. Held every 5 years, the event serves as a way of summarising the CCP’s recent accomplishments, signalling its upcoming trajectories, as well as revealing its top leadership for the next 5-year term. Facing no real opposition, Xi Jinping was chosen to serve a historic third term as General Secretary along six other members of the Politburo Standing Committee, all of who have proven their loyalty to Xi in the past.

There was a lot for the Party to brag about. Over Xi’s past 10 years as General Secretary the country has experienced impressive economic growth, further cementing it as the world’s second-largest economy – since 2012 GDP has increased by over 100% (to $17.73tn in 2021), and the average income has doubled. These positive trends seem to be at a downturn, however, with 19.9% of its youth unemployed, the Chinese Yuan sinking to record lows against the US dollar, and a looming financial crisis centred around falling property prices. In a highly irregular move, the government delayed the publishing of key GDP data during the Congress, with no real justification or alternative publishing date provided.

While Xi may be popular within the Party, that same sentiment does not fully echo in the streets. Public proclamations of dissatisfaction with the government are rare occurrences in China – attempts at criticising the CCP are expertly contained and swiftly dealt with, and the consequences for dissent are severe. Nevertheless, the opening of the Congress prompted protests at Beijing’s Sitong Bridge – a banner calling Xi a ‘national traitor’ could be seen, while another opposed the government’s infamous ‘zero-Covid’ policy. Although the unidentified man responsible for the protest, dubbed ‘Bridge Man’, was swiftly arrested and security levels all over China raised, his act inspired others unsatisfied with the government to voice their support through less dangerous means. His message could be seen written on the doors of public bathrooms or shared anonymously via Apple’s AirDrop service – a method of communication yet unmonitored by government censors.

Although much of the world has tried to move away from Covid-19 restrictions, they are still alive and well in China. Earlier this year we saw major cities like Shanghai placed under harsh restrictions, leaving millions of people locked at home or in centralised quarantine facilities, unable to leave even for the provision of basic necessities. The policy’s impact can be felt even outside of major virus outbreaks, with travel between many cities requiring tests and permission from multiple authorities, as well as lengthy quarantine periods. Not just the people are concerned about the consequences of such restrictions – the World Bank and IMF both lowered China’s predicted GDP growth for this year, to 2.8% and 3.2% respectively (both well below the Party’s target of 5.5%).

Despite this, Xi’s priority remains on preventing any spread of the virus. While possible deaths are definitely an issue—around two-thirds of the Chinese population aged 60 and over is not vaccinated and faces a lack of ICU beds if hospitalised—the CCP recognises not only the increased power it now wields over surveillance and managing the movement of citizens, but also the power that the Covid-19 narrative holds moving into Xi’s third term.

With the country being unable to keep up its hitherto rapid economic development, the Party must look for other avenues of legitimising its rule and keeping citizens content – or create them if necessary. For the first time the use of the word ‘security’ exceeded that of ‘economy’ during a Party Congress. Indeed, Xi’s remarks during the opening days of the event seem to solidify this shift of narrative. Besides praise for the success of the ‘zero- Covid’ policy, centre stage was granted to the topics of maintaining order in Hong Kong, boosting the military, and reserving China’s right to use force in resolving the issue of Taiwan. This correlates with the defence budget rising year-on-year, with a record high of $209bn in 2021.

In many ways, this is a natural continuation of Xi’s ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ agenda, which served as the guiding narrative since he took office in 2012. Having reinvigorated the economy and ‘eradicated’ poverty, the Party can now set its sights on the more ambitious goal of consolidating its power within the territories it lays claims to and closing them off from any threats which may jeopardise ‘national security’ – be it Covid-19, western media and journalism, or democratic liberalisation. Riding on the momentum of ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy and sour relations with the west, China now has the resources and vision to show the world that it will not tolerate attempts at undermining the CCP’s or Xi’s authority – at home or abroad.

In terms of foreign relations, a taste of China’s new approach could be seen even during the Congress. On its opening day a pro-democracy protest was held outside of the Chinese consulate in Manchester. One of the protestors, Bob Chan, a citizen of Hong Kong, was dragged through the consulate’s gate and beaten by the staff. He claims this happened after his attempt at protecting protest banners mocking Xi Jinping from being ripped by the officials. Chinese consul-general Zheng Xiyuan, who was seen pulling Chan’s chair, later commented that it was his ‘duty’ to protect his country and leader from abuse. Not only is this a glimpse of China’s evolving diplomatic strategy, but also a testament to the importance of Xi’s persona in the CCP’s new chapter.

While it may be too soon to draw conclusions on the long-term implications of this shift, it is likely that China will want to appear more powerful in the eyes of its foreign rivals, and solidify the CCP’s role as protector and saviour of its people. Even though the possibility of imminent armed efforts to retake Taiwan seems unlikely, the west will have to tread lightly, as China will most likely be unwilling to suffer similar embarrassment to that evoked by Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August.

Xi Jinping is set to be formally confirmed as president next March, with the world already awaiting China’s next move. Until then, it seems abundantly clear that the era of Deng Xiaoping’s philosophy of ‘hide your strength, bide your time’ is well and truly over. For China, the time is now.

0 Comments